What will be the impact of extending Right to Buy to housing associations?

They say an Englishman’s home is his castle, and the national obsession with owning our own homes shows no signs of going anywhere. So, with one in three millennials unlikely to ever own their own home, according to think tank the Resolution Foundation, it has now been confirmed that the Prime Minister will extend the Right to Buy to allow housing association residents to buy their own homes. We examine the scheme's history and what the proposal could mean.

History

The policy owes its roots to the Conservative Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, who first created a version of the Right to Buy scheme in 1980 when she sold council residents the homes they lived in at discounts of up to 70%. Even then, it was controversial, as it led to a drop in the availability of council housing, despite getting millions into homes of their own. Over the four decades, since it was introduced, stock has eroded further.

The Right to Buy Scheme in 1980 allowed council residents to buy their homes at up to 70% discount.

The Right to Buy Scheme in 1980 allowed council residents to buy their homes at up to 70% discount.

That didn’t deter then Prime Minister David Cameron from looking to increase take-up in 2015 by introducing larger discounts as a means to increase homeownership and appeal to a demographic that didn’t traditionally vote Conservative. While it might have been a vote winner (and indeed, after historic defeats in the recent council elections, it’s no coincidence that Boris Johnson is reverting to the issue now), the idea was beset with complications, including legal ramifications, council resistance and expense. Consequently, it largely stalled even in Cameron’s era.

Housing shortages

Despite Boris’ intended resurrection of Right to Buy for housing association residents, the issues that occurred still exist, the first of which is social housing stock supply. With homeless charity Shelter reporting that the list of people waiting for social housing has reached over two million since the pandemic, allowing the purchase of social housing is bound to exacerbate the gap between the supply of housing and the demand for it.

Chief Executive of Shelter, Polly Neate, has torn into the proposals, saying: “Right to Buy has already torn a massive hole in our social housing stock as less than 5% of the homes sold off have ever been replaced. These half-baked plans have been tried before, and they’ve failed.”

While the government is aiming to build a new house to replace every property sold, the rising costs of building materials due to inflation and Covid-related supply and labour disruptions make this unrealistic. It is now predicted to miss its manifesto target of building an additional 300,000 homes each year in quite some way, and reducing social housing availability seems likely to cause problems rather than solve them. The sharp declines in social housing availability have caused Scotland and Wales to abandon all Right to Buy policies in recent years.

Cost of the scheme

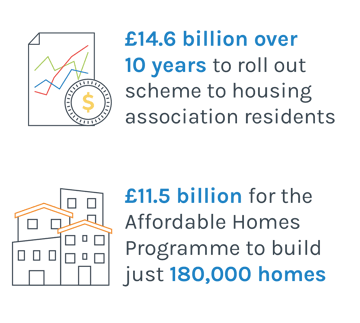

Cost is another issue that could negatively affect the extension of the scheme, with both the cost of the discount and the cost of finding new housing to replace it likely to hit the government coffers hard. A report published by the Voluntary Right to Buy pilot in the Midlands discovered that a roll-out of the scheme would cost the Treasury £14.6 billion over the next ten years, equivalating to 223,843 properties being sold at a discount. Set this against the £11.5 billion it will cost the Affordable Homes Programme to build just 180,000 replacement homes (so not even enough to replace those sold), and the return on investment seems questionable.

A rollout of the scheme is expected to cost the Treasury £14.6 billion—it costs £11.5 billion to build just 180,000 homes.

Legal complexities

There are also legal implications to untangle. Unlike the council houses that Thatcher sold off in the 1980s, housing association buildings are private bodies, and many have debts against them that need to be paid off before they can be sold. Many housing associations also own a large number of homes that they are not legally allowed to sell, as they were acquired under a mandate that they must remain affordable in perpetuity (Section 106). Therefore, while the Right to Buy policy has been designed to help residents in social housing buy the homes they live in, many of those in social housing won’t actually be eligible to take it up. While the Midlands Voluntary Right to Buy pilot attempted to deal with this issue by allowing residents of these homes to apply their Right to Buy discount against another social housing property, the take-up was low – with only 12% of residents offered this opportunity completing a sale.

Demand for the Right to Buy

Indeed, another question mark against the scheme is how many residents are likely to take it up. With the March 2022 Office for National Statistics (ONS) report finding that almost one in four adults are finding it ‘difficult’ or ‘very difficult’ to pay their bills compared to a year ago, the country is facing a cost-of-living crisis. Energy and fuel prices are still rising, and interest rates are expected to go up even further.

Impact on the private sector

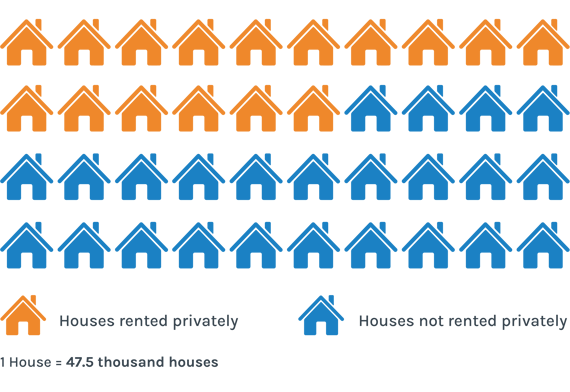

Another criticism levelled at the scheme is what happens to the homes when they’ve been purchased. CEO of DJ Alexander Scotland, David Alexander, notes: “Interestingly, it was the sale of council housing in the 1980s that led directly to the substantial growth of the private rented sector.”

Since the policy was first launched in the 1980s, a total of 1.9 million homes have been sold to residents through the Right to Buy scheme. Research by the Chartered Institute of Housing (CIH) last year found that 40% of the homes sold are now rented out privately, arguably undermining the very principle on which the policy was built.

The re-emergence of the Right to Buy scheme is an interesting proposition. On the one hand, of course, it has merits. Thatcher’s Right to Buy won her legions of voters from beyond her traditional heartland and fulfilled many people’s dreams of homeownership. But the climate has changed, and the government has already accepted that the take-up of the scheme will be significantly less. It’s also likely to cost substantially more. While cynics might argue that Johnson is aiming to emulate Thatcher’s surge in popularity just as much as he’s attempting to advance homeownership, conversely, he might end up alienating more residents than he attracts.

Conclusion

With the scheme going ahead despite criticisms from a broad range of voices, we await further detail to see how tenable it is, and how housing associations will be enticed into accepting it.

As those who work within it know, property management in social housing is extremely demanding, with a huge duty of care to the residents involved, many of whom are vulnerable. Fixflo’s social housing solution ensures that regular maintenance can be planned and scheduled ahead of time, while residents can report repairs swiftly and safely using the 24/7 access online platform.

BLOG DISCLAIMER

This article is intended for information purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. If you have any questions related to issues in this article, we strongly advise contacting a legal professional.

These blog posts are the work of Fixflo and are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. In summary, you are welcome to re-publish any of these blog posts but are asked to attribute Fixflo with an appropriate link to www.fixflo.com. Access to this blog is allowed only subject to the acceptance of these terms.